A vote against Modi

N D Sharma

N D Sharma

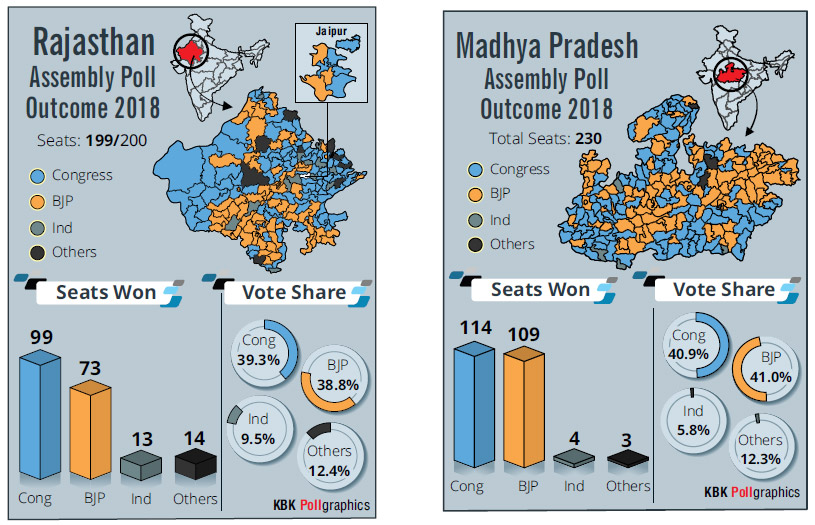

The anti-BJP drift was

visible in all the five

States where Assembly

elections were held in

November-December.

The anti-BJP drift was

visible in all the five

States where Assembly

elections were held in

November-December.

While the electorate

threw away the BJP governments in

Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and

Chhattisgarh, the BJP could barely

win one seat each in Telangana and

Mizoram in spite of having put

forward its candidates in almost all

the constituencies in the two States.

Even though Prime

Minister Narendra Modi’s

two major “achievements”

did not figure prominently

in the high-pitched

campaigns, these two

seemed to have

considerably influenced

the mind of the voters,

particularly in the three

Hindi heartland States of

Rajasthan, Madhya

Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

The scars created by the

demonetisation on the

middle and lower classes

have not healed so far.

The pro and antireservation

agitations

seemed to have

considerably influenced

the voters’ choice in

Madhya Pradesh and

Rajasthan. The

organisations

representing Scheduled

Castes and Scheduled

Tribes were in a militant

mood after the Supreme

Court had diluted the

arrest provisions of the

Scheduled Castes and

Scheduled Tribes

(Prevention of Atrocities)

Act and the Central

government continued

dilly-dallying to undo it.

Ajit Jogi

Similarly, the GST

continues to be a sore

point with the middle rung

traders. Apparently aware

of this the party in the three

States did not seek the vote

in the name of Narendra

Modi but in the names of their chief ministers, Vasundhara Raje

in Rajasthan, Shivraj Singh Chouhan in

Madhya Pradesh and Raman Singh in

Chhattisgarh. In the full page

newspaper advertisements also, the

photos of the chief ministers were

displayed prominently while a small

photo of Narendra Modi was tucked

behind. According to an IndiaSpend

analysis of electoral data, the BJP lost

more than 70 per cent of the Assembly

constituencies where Prime Minister

Narendra Modi campaigned in the five

States.

Ajit Jogi

Similarly, the GST

continues to be a sore

point with the middle rung

traders. Apparently aware

of this the party in the three

States did not seek the vote

in the name of Narendra

Modi but in the names of their chief ministers, Vasundhara Raje

in Rajasthan, Shivraj Singh Chouhan in

Madhya Pradesh and Raman Singh in

Chhattisgarh. In the full page

newspaper advertisements also, the

photos of the chief ministers were

displayed prominently while a small

photo of Narendra Modi was tucked

behind. According to an IndiaSpend

analysis of electoral data, the BJP lost

more than 70 per cent of the Assembly

constituencies where Prime Minister

Narendra Modi campaigned in the five

States.

Narendra Modi and Amit Shah

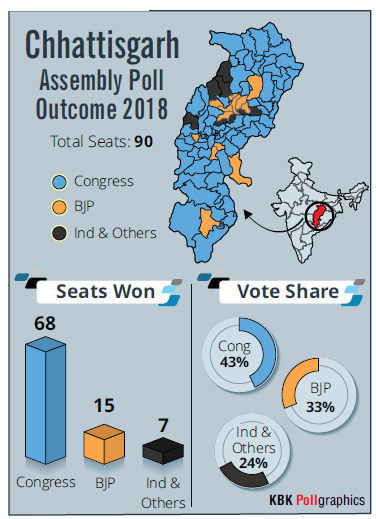

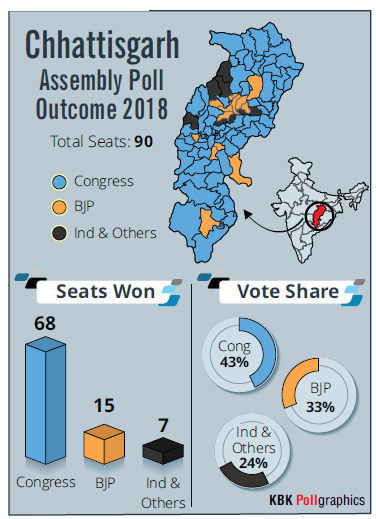

Congress, though, did not appear as

the most favourite party except in

Chhattisgarh where it bagged 68 seats

in a House of 90 reducing the BJP

strength to a mere 15. In the outgoing

House the BJP had 49 members and

the Congress 39. After breaking away

from the Congress, its former Chief

Minister Ajit Jogi had formed his own

party called Janta Congress

Chhattisgarh (JCC) and had entered

into a pre-poll alliance with Mayawati’s

Narendra Modi and Amit Shah

Congress, though, did not appear as

the most favourite party except in

Chhattisgarh where it bagged 68 seats

in a House of 90 reducing the BJP

strength to a mere 15. In the outgoing

House the BJP had 49 members and

the Congress 39. After breaking away

from the Congress, its former Chief

Minister Ajit Jogi had formed his own

party called Janta Congress

Chhattisgarh (JCC) and had entered

into a pre-poll alliance with Mayawati’s

Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Vasundhara Raje and Raman Singh

Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in a bid to

emerge as the alternative to the BJP

and the Congress. But the electorate

decisively shattered his dream and

reposed their faith in the Congress,packing up JCC with 5 and BSP with 2

seats.

Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Vasundhara Raje and Raman Singh

Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in a bid to

emerge as the alternative to the BJP

and the Congress. But the electorate

decisively shattered his dream and

reposed their faith in the Congress,packing up JCC with 5 and BSP with 2

seats.

Mayawati

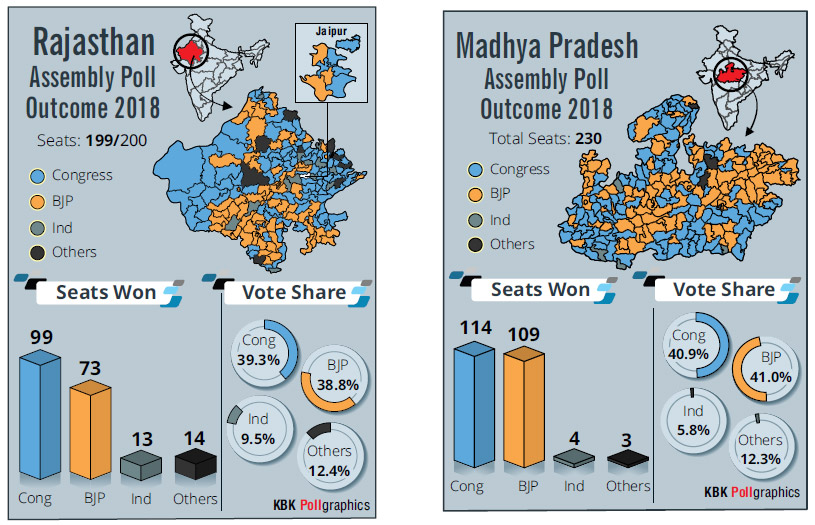

In Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan,

the Congress benefited for lack of a

viable alternative to the BJP and the

Congress. The electorate, therefore,

having made up their minds to oust

the BJP government, voted for the Congress somewhat reluctantly. In

both States, the Congress failed to get

the clear majority. In Madhya Pradesh,

its tally stopped at 114 seats in a House

of 230. The BJP won in 109

constituencies. As many as 120 parties

were in the fray in Madhya Pradesh.

Only two of them could taste victory:

Bahujan Samaj Party got two seats and

Samajwadi Party was able to win one

seat. Four independents also got

through. These seven members lent

their support to the Congress, raising

the strength of the alliance to 121 and,

thus, allowing the Congress to form

the government. Aam Aadmi Party

(AAP) had fielded 208 candidates in

Madhya Pradesh. All but one lost their

deposits, including State head of AAP

and the party’s chief ministerial

candidate Alok Agrawal. AAP’s national

convener Arvind Kejriwal did not

campaign in the State even for once.

Mayawati

In Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan,

the Congress benefited for lack of a

viable alternative to the BJP and the

Congress. The electorate, therefore,

having made up their minds to oust

the BJP government, voted for the Congress somewhat reluctantly. In

both States, the Congress failed to get

the clear majority. In Madhya Pradesh,

its tally stopped at 114 seats in a House

of 230. The BJP won in 109

constituencies. As many as 120 parties

were in the fray in Madhya Pradesh.

Only two of them could taste victory:

Bahujan Samaj Party got two seats and

Samajwadi Party was able to win one

seat. Four independents also got

through. These seven members lent

their support to the Congress, raising

the strength of the alliance to 121 and,

thus, allowing the Congress to form

the government. Aam Aadmi Party

(AAP) had fielded 208 candidates in

Madhya Pradesh. All but one lost their

deposits, including State head of AAP

and the party’s chief ministerial

candidate Alok Agrawal. AAP’s national

convener Arvind Kejriwal did not

campaign in the State even for once.

While in the three

States of Rajasthan,

Madhya Pradesh and

Chhattisgarh, the farm

distress played an

important role in

ousting the ruling BJP,

in Mizoram, the only

State in the north-east

that went to the polls,

prohibition also

played a crucial role in

replacing the Congress

with the Mizo National

Front (MNF) as the

ruling party.

Alok Agrawal

It was ironic that the BJP received

slightly more votes in Madhya Pradesh than the Congress but the Congress

got more seats. The BJP received 41

per cent (1, 56, 42,980 votes) of the

total votes cast while the share of the

Congress was 40.9 per cent (1, 55,

95,153 votes). Besides, in as many as

22 constituencies, the votes cast for

NOTA (none of the above) exceeded

the victory margins of the winning

candidates.

Alok Agrawal

It was ironic that the BJP received

slightly more votes in Madhya Pradesh than the Congress but the Congress

got more seats. The BJP received 41

per cent (1, 56, 42,980 votes) of the

total votes cast while the share of the

Congress was 40.9 per cent (1, 55,

95,153 votes). Besides, in as many as

22 constituencies, the votes cast for

NOTA (none of the above) exceeded

the victory margins of the winning

candidates.

The pro and anti-reservation

agitations seemed to have considerably influenced the voters’

choice in Madhya Pradesh and

Rajasthan. The organisations

representing Scheduled Castes and

Scheduled Tribes were in a militant

mood after the Supreme Court had

diluted the arrest provisions of the

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled

Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act

and the Central government

continued dilly-dallying to undo it.

Agitations were held in the two States,

more violent in Madhya Pradesh.

There has been

“controlled prohibition”

in Mizoram since 2014

– which means that the

people, local or

outsiders, need a

permit to buy alcohol.

There are nearly 50

authorised liquor

shops. The problem

was created by the sale

of alcohol in black

market which

developed a market of

spurious liquor

resulting in deaths. One

of the election

promises of the Mizo

National Front (MNF)

was to bring back total

prohibition if voted to

power.

When the Central government

restored the old draconian provision

through Parliament, it was the turn of

the upper castes to show their

resentment. A new organisation of

general category, OBC and minority

government employees was born

under the name of Sapaks in Madhya

Pradesh. It held demonstrations in

several parts of the State in protest

against the restoration of the stringent

provision in the Act by the Central

government.

As the elections approached,

Sapaks got itself registered as a

political party with the Election

Commission and fielded 110

candidates in the State. It did not win

even a single seat but inflicted damage

on the two main parties, more so on

the BJP. Raghunandan Sharma, a

veteran BJP leader and Rajya Sabha

member, estimates that the BJP lost 15

to 20 seats because of the anger of the

anti-reservationists.

In Rajasthan, too, the Congress

reached near-majority point, getting

99 seats in a House of 200. The

election for one constituency was

countermanded following the death of

a BSP candidate. In 2013, the Congress

had won a mere 21 seats. The BJP had

won 163 seats in the last election. This

time its tally came down to 73, a loss of

90 seats.

BSP got 6 seats, Rashtriya Lok

Tantrik Party (RLTP) 3, CPI (M) and

Bharatiya Tribal Party 2 each, and

Rashtriya Lok Dal 1. As many as 13

independents also got through. Of the

59 SC/ST seats, the BJP could get only

21 while it had won in 50

constituencies in 2013.

It got 12 seats reserved for SCs (as against 32 in 2013)

and 9 ST seats while it was successful

in 18 ST constituencies in the last

election. Rashtriya Lok Tantrik Party

(RLTP) got two seats reserved for SCs

and one was bagged by an

independent. Two ST seats went to

Bharatiya Tribal Party (BTP) and two

were won by independents. Most of

the SC/ST seats were won by the

Congress.

In 2013, the Congress could not win

a single SC seat while 32 were won by

the BJP and one each by the National

People’s Party (NPP) and National

Unionist Zamindara Party (NUZP). Of

the ST seats, the Congress had won a

mere 4 as against 18 by the BJP; two

seats were won by the NPP and one by

an independent candidate.

As the ruling BJP promised free

electricity to farmers as well as to

double farmers’ income, the Congress

promised to usher in “Kisan Raj”. Not

only in Rajasthan, but in Madhya

Pradesh and Chhattisgarh also, the

Congress promised to waive farmers’

loans within ten days of the formation

of the Congress government.

Congress

president Rahul Gandhi went to the

extent of declaring that if the Congress

government was formed and it did not

waive the farmers’ loans within ten

days, the chief minister would be

changed. This seemed to have clicked

with the farming community which

forms a substantial segment of the

electorate in the three States.

While in the three States of

Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and

Chhattisgarh, the farm distress played

an important role in ousting the ruling

BJP, in Mizoram, the only State in the

north-east that went to the polls,

prohibition also played a crucial role in

replacing the Congress with the Mizo

National Front (MNF) as the ruling

party.

There has been “controlled

prohibition” in Mizoram since 2014 –

which means that the people, local or

outsiders, need a permit to buy

alcohol. There are nearly 50

authorised liquor shops. The problem

was created by the sale of alcohol in

black market which developed a market of spurious liquor resulting in

deaths. One of the election promises

of the Mizo National Front (MNF) was

to bring back total prohibition if voted

to power.

One reason cited for

BJP’s failure to impress

the voters in Mizoram

was cited its failure to

keep its promise to

protect the rights of

indigenous tribes in the

north-east.

In a House of 40, the MNF got twothirds

majority with 26 seats while

Congress won only in five

constituencies. The BJP did not forge a

pre-poll alliance. BJP general secretary

in charge of north-east Ram Madhav

had announced much ahead of the

polling day: “we are willing to forge an

alliance with like-minded non-

Congress parties after the elections.”

It

had fielded 39 candidates and had

started talks with regional outfits even

before the election process was

completed, but could win only one

seat in the Chakma-dominated

constituency of Tuichawng.

Chakmas migrated from

Bangladesh over a long period ahead

of Mizoram being made a State in

1986. Young Mizo Association (YMA),

an influential tribal organisation of

Mizoram, has been demanding

scrapping of Chakma Autonomous

District Council (CADC).

Thousands of

protestors had, under the aegis of

YMA, demonstrated at Aizawl alleging

that Mizoram was increasingly

becoming a safe haven for the ‘illegal

Bangladeshi immigrants’ and are now

living, most of them, in refugee camps

in Tripura, following the trouble with

local ethnic groups of Mizoram.

(The

Election Commission enrols them as

voters of Mizoram and makes special

arrangements for their voting.) The

remaining 8 seats were won by

independent candidates.

Zoramthanga

One reason cited for the BJP’s failure to impress the voters in

Mizoram was cited its failure to keep

its promise to protect the rights of

indigenous tribes in the north-east.

The north-east has for decades been

haunted by the illegal influx from the

neighbouring countries and the BJP

has had successes in the north-east

States on its pre-poll promises of

stopping this influx but it did not take

any concrete step towards fulfilling

this promise.

Zoramthanga

One reason cited for the BJP’s failure to impress the voters in

Mizoram was cited its failure to keep

its promise to protect the rights of

indigenous tribes in the north-east.

The north-east has for decades been

haunted by the illegal influx from the

neighbouring countries and the BJP

has had successes in the north-east

States on its pre-poll promises of

stopping this influx but it did not take

any concrete step towards fulfilling

this promise.

Kick-starting his party’s election

campaign, BJP president Amit Shah

declared that Mizoram would

celebrate the next Christmas under

the BJP government. Before

proceeding to Aizawl to launch the

BJP’s election campaign, Shah visited

the Kamakhya temple in Guwahati.

Then he wrote on his official Twitter

handle: “Blessed to have prayed at the Maa Kamakhya devi shaktipeeth in

Guwahati today on Durga Ashtami.:

Interestingly, the MNF is a

constituent of the BJP-led North East

Democratic Alliance (NEDA) but both

MNF and BJP contested the election

separately. MNF president

Zoramthanga, who was sworn in as

the Chief Minister for the third time,

was quoted as having observed: “Due

to Christianity and traditional ethnic

conviction, the Mizos are very closeknit

and deep-bonding society.

A party

like BJP has no space in such a society.

My government would make all-out

efforts to further develop the Mizo

society and the infrastructure of the

State, especially the roads.”

N D Sharma

N D Sharma

Ajit Jogi

Ajit Jogi Narendra Modi and Amit Shah

Narendra Modi and Amit Shah Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Vasundhara Raje and Raman Singh

Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Vasundhara Raje and Raman Singh Mayawati

Mayawati Alok Agrawal

Alok Agrawal Zoramthanga

Zoramthanga