Talaq absolutely irrational !

Anuradha Dutt

Anuradha Dutt

Ensuring gender parity and

upholding human rights

and dignity across the vast

population spectrum are

integral to good

governance. Such crucial

issues often get derailed by political rhetoric

and stratagems, to the detriment of the

democratic ideal. The current impasse over

framing a law against triple talaq so as to

protect vulnerable Muslim women from the

machinations of callous spouses, who can

expel wives from their life by uttering the word

'talaq' thrice, even over the phone, or convey

their intent via email, SMS, other means via the

unfair practice of instant divorce, is a case in

point.

Talaq e biddat or irregular divorce, banned

by many Islamic nations, apparently did not

have the sanction of Prophet Mohammad. But

here, in India, it continues to be deployed with

impunity though jurists, human rights

proponents and progressive Muslims all agree

that the act severely erodes females' dignity

and rights.

The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights

on Marriage) Bill, 2017, passed in the Lok

Sabha where the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party

has a majority, was stalled by the Congress

and like-minded parties in the Rajya Sabha

since the BJP-led coalition lacks sufficient

numbers in the Upper House to ensure

passage of the bill. However, the Union

government is determined to spike this premedieval

practice that has no validity under

secular law, largely prevalent and applicable to

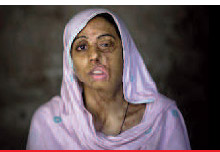

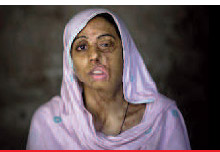

Muslim women suffer

from the machinations

of callous spouses, who

can expel wives from

their life by uttering

the word 'talaq' thrice,

even over the phone, or

convey their intent via

email, SMS, other

means via the unfair

practice of instant

divorce. Talaq e biddat

or irregular divorce,

banned by many Islamic

nations, apparently did

not have the sanction

of Prophet Mohammad.

But here, in India, it

continues to be

deployed with impunity

though jurists, human

rights proponents and

progressive Muslims all

agree that the act

severely erodes

females' dignity and

rights.

Hindus who comprise the majority

community. The Supreme Court, in fact,

banned triple talaq via its August 2017

verdict while ruling on pleas filed by victims

of the practice. It had also directed that a

law in this regard be framed by Parliament

within six months.

The stalemate reportedly is over the

penal provisions in the bill, which

criminalise instant talaq and provide for up

to three years' imprisonment for the

offender, and even enable the presiding

magistrate to impose a hefty fine. The victim

can apply for maintenance for her children

and herself as well as their custody. It was

passed by the Lower House on December

28, 2017.

Opponents of the bill want these

penalties diluted. The Congress's

stonewalling tactics are being ascribed to its

minority appeasement policy, in force since

Independence when the Jawaharlal Nehruheaded

government chose to retain Muslim

Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act,

1937, instituted by the British. In its own

defence the party avers that it supports

abolishing triple talaq but wants the bill to

be modified. The ruling dispensation will

now try to get the bill passed in the Rajya

Sabha during the budget session.

Conservative Muslims aver that reforms

need to be initiated from within the

community, as if the endeavours to bring

about gender parity by victims of

reprehensible customs such as instant

divorce and nikah halala are invalid.

The former's obduracy underlines the

subordinate position accorded to females

under personal law, which is contrary to the

constitutional guarantee of equality of all

citizens. Three decades ago, the reforms bid

fell through when the Rajiv Gandhi-headed

government chose to revoke the Supreme

Court directive for payment of maintenance

– a meagre Rs 125 a month after the threemonth

iddat period - by a man who had

divorced his 70-year-old wife Shah Bano via

talaq e biddat. Muslim Women (Protection

of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 scuttled the

reforms attempt.

The former's obduracy underlines the

subordinate position accorded to females

under personal law, which is contrary to the

constitutional guarantee of equality of all

citizens. Three decades ago, the reforms bid

fell through when the Rajiv Gandhi-headed

government chose to revoke the Supreme

Court directive for payment of maintenance

– a meagre Rs 125 a month after the threemonth

iddat period - by a man who had

divorced his 70-year-old wife Shah Bano via

talaq e biddat. Muslim Women (Protection

of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986 scuttled the

reforms attempt.

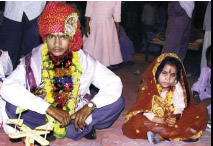

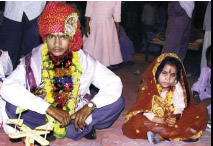

Under Hindu customary laws too

females were accorded an inferior position

until the British Raj and free India's rulers

intervened. Regressive customs such as

child marriage, sati and female infanticide

were banned by the British, who also

promoted widow remarriage and girls'

education among Hindus. Sati was banned

in Bengal Presidency in 1829 and in gradual

stages in other parts. In 1929 the Child

Marriage Restraint Act was passed. And,

polygamy was outlawed almost three

decades later, in 1955-1956, with

enactment of Hindu Code Bill. Every

initiative was strongly opposed by

custodians of the old order.

Under Hindu customary laws too

females were accorded an inferior position

until the British Raj and free India's rulers

intervened. Regressive customs such as

child marriage, sati and female infanticide

were banned by the British, who also

promoted widow remarriage and girls'

education among Hindus. Sati was banned

in Bengal Presidency in 1829 and in gradual

stages in other parts. In 1929 the Child

Marriage Restraint Act was passed. And,

polygamy was outlawed almost three

decades later, in 1955-1956, with

enactment of Hindu Code Bill. Every

initiative was strongly opposed by

custodians of the old order.

The difficult task of codifying Hindu laws

of marriage and divorce, adoption,

succession and related matters on secular

and equitable lines was accomplished

under the supervision of Dr B.R. Ambedkar,

first law minister of free India. The

constitutional pledge of equal rights to

citizens, irrespective of caste, religion and

gender, was meant to ensure parity.

The difficult task of codifying Hindu laws

of marriage and divorce, adoption,

succession and related matters on secular

and equitable lines was accomplished

under the supervision of Dr B.R. Ambedkar,

first law minister of free India. The

constitutional pledge of equal rights to

citizens, irrespective of caste, religion and

gender, was meant to ensure parity.

Monogamy was made the rule for adult

Hindu males; child marriage and sati

banned; divorce and widow remarriage

allowed; alimony provided to women by

former spouses; daughters accorded

coparcenary right, at par with sons', to

father's self-acquired property, and under

Hindu Succession Act 1956, wherever

Dayabhag law was followed, to ancestral

property. Daughters' right to ancestral

property, at par with sons', was extended to

other parts by the 2005 amendment to the

act at the behest of the Congress regime at

the Centre.

Duplicity is inherent

in the retention of the

savarna pyramid – that

is caste system of

graded inequality –

formulated in Laws of

Manu, a repressive

Christian millennium

law book that has

outlived its time, as the

fulcrum of identity

politics and policy of

reservations in

government jobs and

educational

institutions. Since

Manusmriti's criminal

code has been

discarded, there is no

rationale for factoring

caste into the planning

and development

process, which is better

driven by economic

indices.

Demanding dowry and female

infanticide were made cognisable offences.

Caste-based discrimination and

untouchability were also banned. Violations incurred punishment. Hindu law applied also

to Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists, minority groups.

They were entitled to follow their own

customs. Interestingly, giving and receiving

dowry, considered unIslamic, is now common

among Muslims.

The 2011 national census estimated

Muslim numbers at 17.22 crore, comprising

14.23 per cent of the population. In denying

justice to numerous victims of archaic laws

that weigh against females - originating in

West Asia and prevalent mainly among Sunni

Muslims - policymakers would be defaulting

on their duty to help a vulnerable segment

integrate into the mainstream. The Shah Bano

case is still cited as one of the most glaring

instances of missed opportunity for the Rajiv

Gandhi government to bring the Muslim

community under the ambit of secular law,

which would have paved the way for

implementing the constitutional directive for a

uniform civil code.

To quote English poet John Donne, "No

Man is an island, entire of itself; / every man is

a piece of the continent, / a part of the main".

Fortunately, customary criminal laws are

not implemented. Otherwise, death by

stoning for adultery, as enjoined by the Islamic

Shariah, and an adulterous wife being eaten

up by dogs or paraded on donkeys, prescribed

by Manusmriti, would have been the norm.

Similarly, Manusmriti condemns

homosexuality. It recommends atonement

for sex between members of the same

gender.

Depending on the nature of the act, these

vary from a purifying bath while clothed;

payment of a fine; to shaving of the head; or

chopping of two fingers and being paraded on

a donkey. Proponents of revoking Article 377

who cite India's supposed past liberality in

support of their case should take note of this.

Duplicity is inherent in the retention of the

savarna pyramid – that is caste system of

graded inequality – formulated in Laws of

Manu, a repressive Christian millennium law

book that has outlived its time, as the fulcrum

of identity politics and policy of reservations in

government jobs and educational institutions.

Since Manusmriti's criminal code has been

discarded, there is no rationale for factoring

caste into the planning and development

process, which is better driven by economic

indices.

The writer is a seasoned

journalist and author.

Anuradha Dutt

Anuradha Dutt